Crip Lit

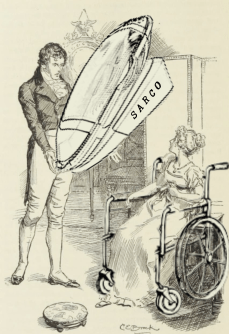

Mr Ableism Proposes to Dispose of Miss Cripple Using the Sarco Death Pod

deathstyles of the rich & abled, MALE-PATTERN BS, REGENCY CRIP LIT

It is a truth universally acknowledged that a woman in possession of a neurodegenerative disease must be in want of an early death.

My dear Miss Cripple,

Mr Abled’s proposal so enraged her that she could only reply, “You first, sir” when he presented her with a Sarco Death Pod of betrothal.

Madam, in vain I have struggled. It will not do. My feelings will not be repressed. You must allow me to tell you how ardently I pity you and plead you to accept my assistance in hastening your death using the Sarco Death Pod on its Delicates & Gentlewomen setting.

In declaring myself thus, I am fully aware that I will be going expressly against the notion of a healthcare system that prioritizes people over profit, the rights of many people with disabilities, and, I hardly need add, my own better judgment.

But, as you may have heard, “civil rights” for unfortunates such as yourself are now largely reserved for your demise. Particularly when a gentleman such as your father has five daughters and only a small income. How may such as he afford to see your sisters wed if you and your costly care refuse to be dead? Continue reading