disability narrative

A Crip in Philanthropy: The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times: This Moment in Disability, Dignity, and Human Rights

An earlier version of these remarks was shared at Congregation Beth Jacob in Redwood City, California on March 3, 2018. I deeply appreciated their welcome when I was invited to address their community by Anne Cohen, an activist, disabled parent, and board member at the organization where I am Director of Development, Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund (DREDF) or, as Anne has dubbed it, “the ACLU of disability rights.” CBJ’s cross-disability access allowed me to take the first step in organizing community support: communicate.

An earlier version of these remarks was shared at Congregation Beth Jacob in Redwood City, California on March 3, 2018. I deeply appreciated their welcome when I was invited to address their community by Anne Cohen, an activist, disabled parent, and board member at the organization where I am Director of Development, Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund (DREDF) or, as Anne has dubbed it, “the ACLU of disability rights.” CBJ’s cross-disability access allowed me to take the first step in organizing community support: communicate.

I grew up with a disability, one that is genetic. I have been a plaintiff in an ADA access case here in California. It involved a bathroom. That required a lot of talking publicly about my using the bathroom. For disabled people like me – physically disabled — being disabled means never knowing where your next accessible public bathroom is. Today. Nearly thirty years after the ADA was passed. And keep in mind those 30 years coincide with my fundraising career in social justice non-profits and their philanthropic allies. Those are whole decades of trying my best to use empathy and imagination to shift that stubborn disability narrative that says I receive but can’t give. That disability is a health thing. That I need a cure when a toilet would be preferable. That I am charity, personified, not justice, denied.

There’s No Cure for Gretchen Lowe: A Mother’s Day Card From Alice

Alice’s schoolteacher handwriting greeted Gretchen when she flipped through the mail that evening. It was a floridly pious Mother’s Day card with a letter enclosed. Her mother must have sent it right after Gretchen had called about the board meeting fiasco. Oh Alice, Gretchen snorted pleasurably. I couldn’t have picked a better card myself.

Alice’s schoolteacher handwriting greeted Gretchen when she flipped through the mail that evening. It was a floridly pious Mother’s Day card with a letter enclosed. Her mother must have sent it right after Gretchen had called about the board meeting fiasco. Oh Alice, Gretchen snorted pleasurably. I couldn’t have picked a better card myself.

Underneath the card’s summary appreciation for maternal sacrifices, physical and emotional, Alice had written, “Thought you might like to see the enclosed item right now. I think it confirms that we are related. I cannot take credit for why you are who you are but I did have a hand in it. Then again, you were always a rotten child. Not that I had anything to do with that. Love, Mom.

The letter was her mother’s same handwriting. Cheered, Gretchen set to reading it. It was dated from May 1970 and addressed to a Desmond Wallace, Chair of Fundraising Operations for the National Cerebral Palsy Association. Oh dear.

#CripLit Chapter 2: Funktionslust

Before I Resist and Persist, I Must Exist: Bioethical Choice, Living “Like That,” and Working the Early Shift of Cleaning Up Ableist Narratives

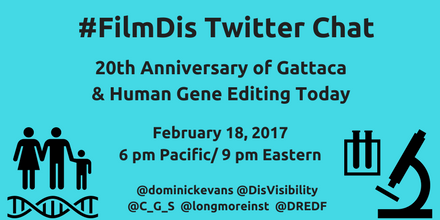

I represented DREDF in this conversation but it’s stirred up a big case of the feels about “choice” and being a liberal woman writer with a congenital disability, and the context this establishes for storytelling, and resisting and persisting. I continue, after 30 years of adult activism, to feel like I have an early shift of ableism — prepping the world to accept that I exist — while my nondisabled fellow human resisters and persisters get to sleep in. And if I weren’t white, conventionally educated, cis gendered, unthreateningly queer, and had all sorts of middle-class, married advantages, I’d probably never sleep at all. Image courtesy of the Disability Visibility Project.

I represented DREDF in this conversation but it’s stirred up a big case of the feels about “choice” and being a liberal woman writer with a congenital disability, and the context this establishes for storytelling, and resisting and persisting. I continue, after 30 years of adult activism, to feel like I have an early shift of ableism — prepping the world to accept that I exist — while my nondisabled fellow human resisters and persisters get to sleep in. And if I weren’t white, conventionally educated, cis gendered, unthreateningly queer, and had all sorts of middle-class, married advantages, I’d probably never sleep at all. Image courtesy of the Disability Visibility Project.

Step 1: I Exist!

As many people who know me know — all too well — I’ve been writing a novel* for the past 400 years or so. The novel, The Cure for Gretchen Lowe, is the exploration of a what-if premise: What if a congenitally disabled woman were offered an experimental therapy that would cure her? The cure itself, Genetic Reparative Therapy (GRT), was never the point of the story because biomedical research, real or invented, never seemed like the most interesting part of the story. What I’ve been stuck on, like an oyster (or barnacle), since the idea first irritated my imagination was how I saw that my character’s situation began as a will-she-or-won’t-she question. From what I’ve observed in 50+ years of congenitally disabled life, that question isn’t typically a question to The Average Reader. “Well, of course a person like that would want GRT!”

I’ve considered that point of view quite a bit — 400 years allows for that — and much more seriously than I make it sound here. But that assumption also irritated me mightily: As a lifelong like-that-ter, I’ve run up against a lot of nonconsensual of-coursing when it comes to my bioethical choices. Simply opening my story — which I refer to as being “CripLit” — with a genuine choice, not a pro forma one, felt like I wrote in letters across the sky: I EXIST.