A Crip in Philanthropy (CRiP)

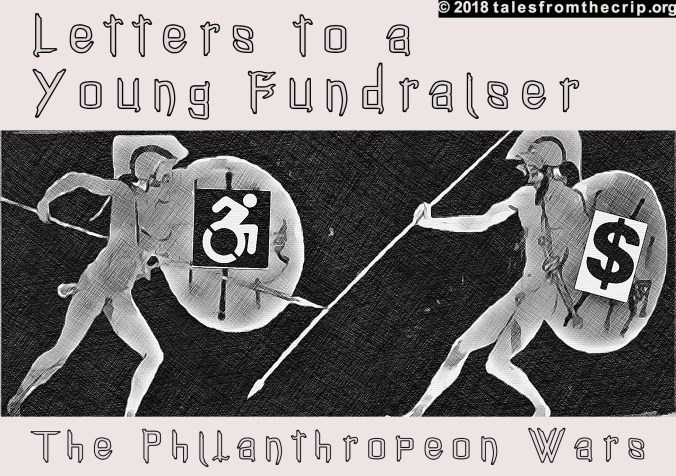

Letters to a Young Fundraiser: The Philanthropeon Wars and the Fall of Telethonika

My Dear Friend:

You wrote of a growing strain on your spirit that seems to have no reasonable source, as your position is unobjectionable, your master provides you accommodations enough, and your annual fundraising goal numbers not unduly burdensome. What then?

You ask if you are perhaps “a loser.” I think not.

During my youth, my father — a fundraising titan who fought for funding alongside Major Donor — became disgusted with my inadequate Girl Scout cookie sales and sent me away to a notorious fundraising academy, one of the very strictest of the Transactional schools.

I was miserable and branded a failure — a loser — at “working the room,” and “friend-raising,” and so on, until I was confined to the barracks for insubordination after I refused to ply my trade at a memorial service, trading donations for signatures in the guest book.

But then I took a History of Fundraising in Western Civilization class. I learned about the Philanthropeon Wars.

I learned about the lost city-state of Telethonika, where disability democracy had been born around the year 504 BC. It is a loss that echoes down through millennia through some fundraisers who have the disability consciousness and who feel the shadow each year as Labor Day approaches. You may be feeling the echo of the fall of Telethonika, that flattish plain located one mountain over from Sparta.

A Crip in Philanthropy: The Best of Times, the Worst of Times

The Best of Times, the Worst of Times: This Moment in Disability, Dignity, and Human Rights

An earlier version of these remarks was shared at Congregation Beth Jacob in Redwood City, California on March 3, 2018. I deeply appreciated their welcome when I was invited to address their community by Anne Cohen, an activist, disabled parent, and board member at the organization where I am Director of Development, Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund (DREDF) or, as Anne has dubbed it, “the ACLU of disability rights.” CBJ’s cross-disability access allowed me to take the first step in organizing community support: communicate.

An earlier version of these remarks was shared at Congregation Beth Jacob in Redwood City, California on March 3, 2018. I deeply appreciated their welcome when I was invited to address their community by Anne Cohen, an activist, disabled parent, and board member at the organization where I am Director of Development, Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund (DREDF) or, as Anne has dubbed it, “the ACLU of disability rights.” CBJ’s cross-disability access allowed me to take the first step in organizing community support: communicate.

I grew up with a disability, one that is genetic. I have been a plaintiff in an ADA access case here in California. It involved a bathroom. That required a lot of talking publicly about my using the bathroom. For disabled people like me – physically disabled — being disabled means never knowing where your next accessible public bathroom is. Today. Nearly thirty years after the ADA was passed. And keep in mind those 30 years coincide with my fundraising career in social justice non-profits and their philanthropic allies. Those are whole decades of trying my best to use empathy and imagination to shift that stubborn disability narrative that says I receive but can’t give. That disability is a health thing. That I need a cure when a toilet would be preferable. That I am charity, personified, not justice, denied.

The Crip Sense: “I See Women and Girls With Disabilities. In Your Organizations.”

In my particular line of work — fundraising — I have the “challenge” of making the case for funding cross-disability civil rights work from institutional funders who are still predominately stuck in the disability = tragedy trope.

I need allies from outside the cross-disability communities because that’s how philanthropy — and everything else — works: it’s who you have relationships with, who you can ask for help, give help to.

I was really excited about closing out Women’s History Month this year by developing and delivering an interactive workshop, “Building Your Organization’s Capacity to Ally With Girls Who Have Disabilities: Principles to Practices” for fellow (sister?) Alliance for Girls members, as part of my work at DREDF. (To the members who attended — you were GREAT participants!) Based on issues I’d recently written about, I wanted to call it “The Crip Sense or ‘I See Women and Girls With Disabilities. In Your Organizations.’” (Scroll down for 3 “posters” of workshop content.)

I said that part of having The Crip Sense is seeing things that are painful:

- Disability human and civil rights violations. Way too many of them.

- Violence against disabled children and adults – especially people of color (PoC) with invisible disabilities — even by caregivers, school personnel, and law enforcement officers, and that such violence at home, in school, and on the street is excused or rationalized.

- Girls who have internalized stigma that makes it feel “normal” to disown, downplay, or deny having a disability.

- Girls who hear – even from some disabled people – that “initiative” and “personal responsibility” can defeat systemic barriers born of — and well-maintained by — prejudice, and that they’ve failed if they’re defeated by rigged systems.

Why This Workshop, Why Now

In 2017, an inclusive movement includes cross-disability civil rights organizations, as a given.

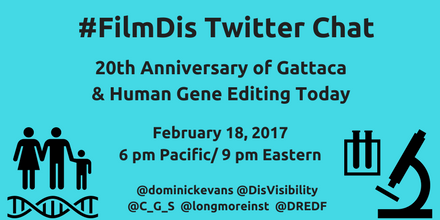

Before I Resist and Persist, I Must Exist: Bioethical Choice, Living “Like That,” and Working the Early Shift of Cleaning Up Ableist Narratives

I represented DREDF in this conversation but it’s stirred up a big case of the feels about “choice” and being a liberal woman writer with a congenital disability, and the context this establishes for storytelling, and resisting and persisting. I continue, after 30 years of adult activism, to feel like I have an early shift of ableism — prepping the world to accept that I exist — while my nondisabled fellow human resisters and persisters get to sleep in. And if I weren’t white, conventionally educated, cis gendered, unthreateningly queer, and had all sorts of middle-class, married advantages, I’d probably never sleep at all. Image courtesy of the Disability Visibility Project.

I represented DREDF in this conversation but it’s stirred up a big case of the feels about “choice” and being a liberal woman writer with a congenital disability, and the context this establishes for storytelling, and resisting and persisting. I continue, after 30 years of adult activism, to feel like I have an early shift of ableism — prepping the world to accept that I exist — while my nondisabled fellow human resisters and persisters get to sleep in. And if I weren’t white, conventionally educated, cis gendered, unthreateningly queer, and had all sorts of middle-class, married advantages, I’d probably never sleep at all. Image courtesy of the Disability Visibility Project.

Step 1: I Exist!

As many people who know me know — all too well — I’ve been writing a novel* for the past 400 years or so. The novel, The Cure for Gretchen Lowe, is the exploration of a what-if premise: What if a congenitally disabled woman were offered an experimental therapy that would cure her? The cure itself, Genetic Reparative Therapy (GRT), was never the point of the story because biomedical research, real or invented, never seemed like the most interesting part of the story. What I’ve been stuck on, like an oyster (or barnacle), since the idea first irritated my imagination was how I saw that my character’s situation began as a will-she-or-won’t-she question. From what I’ve observed in 50+ years of congenitally disabled life, that question isn’t typically a question to The Average Reader. “Well, of course a person like that would want GRT!”

I’ve considered that point of view quite a bit — 400 years allows for that — and much more seriously than I make it sound here. But that assumption also irritated me mightily: As a lifelong like-that-ter, I’ve run up against a lot of nonconsensual of-coursing when it comes to my bioethical choices. Simply opening my story — which I refer to as being “CripLit” — with a genuine choice, not a pro forma one, felt like I wrote in letters across the sky: I EXIST.